by Bruce Hodsdon

Bruce Hodsdon has contributed in recent years to online publications, Senses of Cinema and Film Alert.

The IFG is a striking example of an innovative concept for a hard copy publication ultimately being reduced to non viability, if not actual irrelevance, by the Internet. While the editors were not able to fully match the breadth of Wikipedia’s coverage of world production data, many of the reports in the Guide by correspondents from the country concerned, both foreshadow and complement Wiki’s factual assemblage, by nation state, of film industry histories and statistics (see links in addenda below).

In asserting its importance, Galt and Schoonover (in their Introduction to Global Art Cinema) see that, from its beginnings, “art cinema forged a relationship between the aesthetics and the geopolitical, in other words, between cinema and the world…a dynamic and contested terrain where film histories intersect with larger theoretical questions of the image and its travels.” They see “new shapes and boundaries” outlined as “rejecting the logic of ever burgeoning markets as well as conventional progressive histories of styles and myths of transmission from the core to the periphery.” (p.3) In this context the IFG offers a kind of work in progress a form of historical document coalescing in a fluid relationship with notions of the art film, the national and the global.

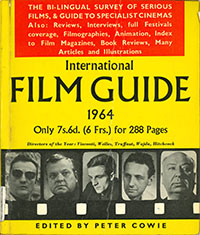

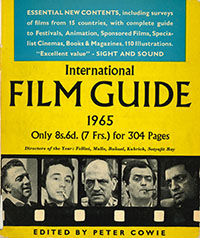

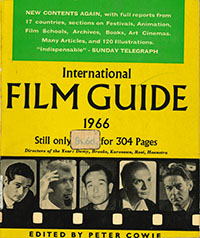

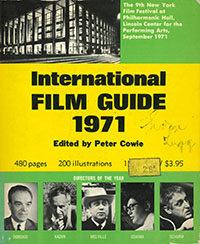

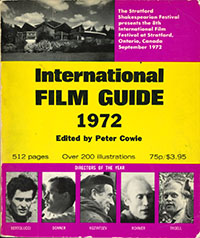

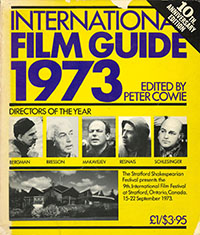

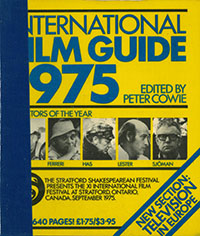

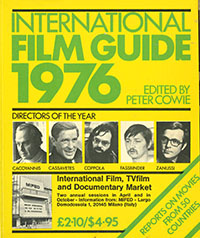

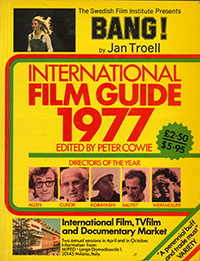

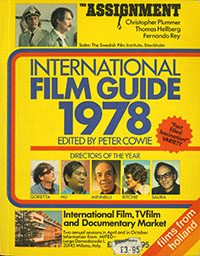

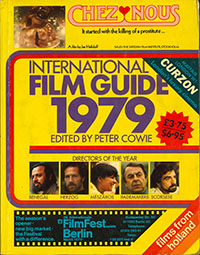

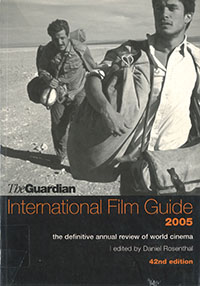

The publication in 1964 of the first issue of the International Film Guide, the brainchild of its founding editor Peter Cowie, was a mark of the emerging concept of an art cinema as something of a hybrid alternative to Hollywood at various points intersecting with popular genres, national cinemas, engagé and avant-garde filmmaking. The Guide purported to be “a definitive annual survey of contemporary global cinema” as it unfolded year by year over five key decades.

The publication in 1964 of the first issue of the International Film Guide, the brainchild of its founding editor Peter Cowie, was a mark of the emerging concept of an art cinema as something of a hybrid alternative to Hollywood at various points intersecting with popular genres, national cinemas, engagé and avant-garde filmmaking. The Guide purported to be “a definitive annual survey of contemporary global cinema” as it unfolded year by year over five key decades.

Peter Cowie, in introducing the first issue of the IFG in 1964, states that the annual is intended “for all those interested in serious cinema (for want of a better term).” He refers to a similar attitude seemingly to be growing all over Europe, among filmgoers and filmmakers alike, “that quality will triumph.” Cowie hastens to add that “this is not to imply that all fine films will be made by a handful of individual artists like Bergman, Antonioni, Resnais or Buñuel. Directors of the calibre of David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia) and Bernhard Wicki (Das Wander des Malachais/The Miracle of Father Malachia) have shown that first-class films can be produced almost in spite of a [relatively] huge budget.”

The promotion of the notion of art cinema was an editorial priority of the IFG. In the 40th issue in 2003 Cowie observes nostalgically that the “IFG struggled into existence during the effervescent age when everything from music to fashion was in ferment. Every month yielded a discovery…The art house cinemas beckoned like temples at which to worship exotic auteurs…Forty years ago, the cinema’s centre of gravity was Europe. Today it hovers in mid-Atlantic, with both Hollywood and the independent sector throwing up works as fascinating and talented as any produced in the vanished 1960s.” His primary initial focus, seemingly appropriate for the times, was support for the growth of specialist art cinemas and film distribution in Britain and North America. He claimed as an innovation in his first (1964) editorial, the publication of a tour guide to such cinemas in Britain, on the Continent, and in the USA. Cowie was also quick to recognise, beginning in the first issue of IFG, the international film festival network then in its relatively early phase pre-video, as providing a base for access to art cinema.

In the editorial for the 25th (1988) edition, Cowie notes the disappearance of the specialist art cinema, which he had earlier described as “havens of quality, places run with love and round-the-clock dedication by individuals in Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam, London, San Francisco, and of course Dan Talbot in New York.” Cowie recalls that fifty pages had been devoted to such cinemas in the first issue of IFG in 1964. He attributes the demise of the concept of the art-house “as a place apart,” to the The Godfather which he claims to be “the first movie to break box office records and to justify the closest analysis by critics and film students.” By the late eighties the specificity of an ‘art-house’ location had yielded to the economics of multiplex exhibition in combination with the greatly expanding international film festival network.

The World Production Survey

Peter Cowie deserves acknowledgement for initiating a more internationalist approach to cinema through the concept of annually bringing together individual country-based production surveys in a single publication. Having established a format for the IFG, the editors worked to expand and refine the production survey, the ‘life blood’ of the publication.

Peter Cowie deserves acknowledgement for initiating a more internationalist approach to cinema through the concept of annually bringing together individual country-based production surveys in a single publication. Having established a format for the IFG, the editors worked to expand and refine the production survey, the ‘life blood’ of the publication.

The early issues of IFG illustrate the hold of art cinema’s foundational Eurocentrism on film culture, global reach charted only by the inclusion of Satyajit Ray and a few Japanese directors. Even two decades later, in describing this process in terms of cultural loss rather than the result of a shifting geographical force field, the founding editor of IFG seems not to have fully come to terms with IFG’s own remapping of the international “from the centre to the periphery” model.

The world production survey, spanning five decades, takes up to about two-thirds of the contents of each issue of IFG. In addition there are special dossiers in some issues with approximately 15-40 pages on film production in selected (initially mainly European or North American) countries. I have outlined and partially indexed some of the surveys’ scope below. In devoting its two main sections to national feature film production and the growth of film festivals, the IFG explicitly notes their linkage. The inclusion of feature films in a major festival is noted in the individual surveys as a form of validation for the local cinema.

The world production survey, spanning five decades, takes up to about two-thirds of the contents of each issue of IFG. In addition there are special dossiers in some issues with approximately 15-40 pages on film production in selected (initially mainly European or North American) countries. I have outlined and partially indexed some of the surveys’ scope below. In devoting its two main sections to national feature film production and the growth of film festivals, the IFG explicitly notes their linkage. The inclusion of feature films in a major festival is noted in the individual surveys as a form of validation for the local cinema.

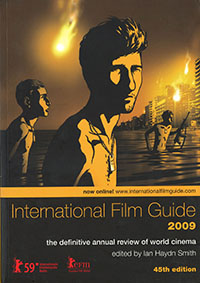

From the first issue the centrepiece of the IFG is the country by country summary of feature film production for the previous year by a special correspondent. The first issue contained only thirteen such reports usually consisting of a brief introductory paragraph and a short review of three or four notable films of the year with a select listing of ‘new and forthcoming films’ by an often anonymous reviewer. By 1972 the number had expanded to 32 reports, 50 in 1978, 65 in 1986, 76 in 2004, 97 (including the addition of 21 short notes) in 2005, peaking with the coverage of 123 countries (including 45 short notes) in 2009 coming close to the long term editorial aspiration of global coverage of all countries producing feature films. From 1970 each correspondent was identified, a significant enhancement of authority and incentive for coherence in the reports. The most consistent were potentially those with the same correspondent over an extended period.

The annual reports for France were made by noted critic and editor of Positif, Michel Ciment, 1971-2012, a record 42 years for IFG. Italy from the first issue is covered by only three correspondents in 43 years and Spain by five beginning in 1968 with two for Portugal from 1995. Film industry insider, Uma du Cunha, reported from India for 36 years from 1977. Australia is well served by three correspondents in 45 years: John Baxter from 1968-70 the years leading into the film revival, David Stratton delivering for 32 years, 1971-2002, with Peter Thompson covering the years 2003-11. In contrast the USA had 14 correspondents, and GB/England/UK 13 over the same period; the question of identity for the “dis-United Kingdom” is never fully resolved. Although New Zealand was one of the early inclusions in the World Survey in 1966 there was no regular production of feature films until the Film Commission was established in 1979, the formative decade, 1973-84, being reported by Lindsay Shelton.

For 33 years from 1968-2000, Variety reporter and teacher Gerald Pratley was the IFG correspondent from Canada. His on-going theme is the identity crisis of Anglophone Canadian feature filmmaking that he describes as “overwhelmed… by the great American presence,” the subject of a ‘mid term’ report by Pratley in 1988. David Cronenberg, an ‘international’ rather than ‘Canadian’ filmmaker, and Atom Egoyan, were the two distinctive auteurs to make most impact internationally. Egoyan was the most prominent of what became known as the Toronto new wave of cinéastes, in the 80s and 90s taking up the legacy of films by Don Owen and Donald Shebib in rejecting Hollywood formulae.

For 33 years from 1968-2000, Variety reporter and teacher Gerald Pratley was the IFG correspondent from Canada. His on-going theme is the identity crisis of Anglophone Canadian feature filmmaking that he describes as “overwhelmed… by the great American presence,” the subject of a ‘mid term’ report by Pratley in 1988. David Cronenberg, an ‘international’ rather than ‘Canadian’ filmmaker, and Atom Egoyan, were the two distinctive auteurs to make most impact internationally. Egoyan was the most prominent of what became known as the Toronto new wave of cinéastes, in the 80s and 90s taking up the legacy of films by Don Owen and Donald Shebib in rejecting Hollywood formulae.

French-Canadian features are supported in Québec’s cinemas as indigenous. The breakthrough for Québécois cinema came with the opening of a French studio at the Montréal-based Canadian National Film Board and la nouvelle vague influenced Le Chat dans la Cat (1964) directed by Gilles Groulx, and later Claude Jutra’s acclaimed Mon oncle Antoine (1971). After breaking Québec box office records, runaway international success came at an important time for French-Canadian film with Le déclin de l’empire Américain (1986) written and directed by Denys Arcand. Feminist filmmaker Léa Pool came into film festival prominence with La Femme de l’Hôtel (1984) and Anne Triste (1986). The success of Québec cinema is the subject of a report by Jamie Graetz in IFG’s 25th 1988 edition.

French-Canadian features are supported in Québec’s cinemas as indigenous. The breakthrough for Québécois cinema came with the opening of a French studio at the Montréal-based Canadian National Film Board and la nouvelle vague influenced Le Chat dans la Cat (1964) directed by Gilles Groulx, and later Claude Jutra’s acclaimed Mon oncle Antoine (1971). After breaking Québec box office records, runaway international success came at an important time for French-Canadian film with Le déclin de l’empire Américain (1986) written and directed by Denys Arcand. Feminist filmmaker Léa Pool came into film festival prominence with La Femme de l’Hôtel (1984) and Anne Triste (1986). The success of Québec cinema is the subject of a report by Jamie Graetz in IFG’s 25th 1988 edition.

Almost invariably the reports on the USA, particularly for the important transition decades of the sixties and seventies, are the least satisfactory in the lack of overall coherence and incisiveness required in the limited space available to cover the scale and diversity of American film production. The format of at best a brief statement of a few industry trends and gross box office receipts accompanied by up to about half a dozen “notable feature films” at times seemingly arbitrarily selected for mini-review, never really succeeds in achieving something like a satisfactory balance between auteur-based summary and industry review. Eddie Cockrell (2001-09), and to a lesser extent Diane Jacobs (1981-6), come closest, in my view, to maintaining a coherent distinction between mainstream Hollywood and independently produced feature films.

Almost invariably the reports on the USA, particularly for the important transition decades of the sixties and seventies, are the least satisfactory in the lack of overall coherence and incisiveness required in the limited space available to cover the scale and diversity of American film production. The format of at best a brief statement of a few industry trends and gross box office receipts accompanied by up to about half a dozen “notable feature films” at times seemingly arbitrarily selected for mini-review, never really succeeds in achieving something like a satisfactory balance between auteur-based summary and industry review. Eddie Cockrell (2001-09), and to a lesser extent Diane Jacobs (1981-6), come closest, in my view, to maintaining a coherent distinction between mainstream Hollywood and independently produced feature films.

Reports from other major film producing countries such as Japan, the USSR/Russia, Scandinavian and Eastern European countries, Hong Kong and South Korea, following a similar format generally achieve better balance and continuity than the reports from the anglosphere. Lindsay Anderson writing from a historical perspective on the state of the British cinema in the 1984 IFG acknowledges “the challenge of complexity.” More so the complexities of scale providing the challenge for reports on the American cinema matched only by those on the Indian film industry.

Reports from other major film producing countries such as Japan, the USSR/Russia, Scandinavian and Eastern European countries, Hong Kong and South Korea, following a similar format generally achieve better balance and continuity than the reports from the anglosphere. Lindsay Anderson writing from a historical perspective on the state of the British cinema in the 1984 IFG acknowledges “the challenge of complexity.” More so the complexities of scale providing the challenge for reports on the American cinema matched only by those on the Indian film industry.

The post war West German cinema is initially in the 1967 Film Guide, East Germany being added as a separate report the following year, the first stirrings of the young West German cinema also being noted. Sweden (67) and Denmark (68) are followed by Finland and Norway in the mid-seventies. Co-productions, now the dominant form of financing in the EU, have been especially important for the small bi-lingual film industry in Belgium first reported on in the 1968 issue. The country’s rich film culture has produced filmmakers of the diverse calibre of documentarist Henri Storck, animator Raoul Servais, André Delvaux, Jean-Jacques Andrien, Chantal Akerman and the Dardenne brothers.

The post war West German cinema is initially in the 1967 Film Guide, East Germany being added as a separate report the following year, the first stirrings of the young West German cinema also being noted. Sweden (67) and Denmark (68) are followed by Finland and Norway in the mid-seventies. Co-productions, now the dominant form of financing in the EU, have been especially important for the small bi-lingual film industry in Belgium first reported on in the 1968 issue. The country’s rich film culture has produced filmmakers of the diverse calibre of documentarist Henri Storck, animator Raoul Servais, André Delvaux, Jean-Jacques Andrien, Chantal Akerman and the Dardenne brothers.

In eastern Europe, the Polish, Hungarian and Czech cinemas are all acknowledged in the first issue (1964). Bulgarian and Yugoslav cinemas make their first appearance in the 1970 IFG, the latter subsequently fragmenting into reports from Croatia (1993), Slovenia (1994), Serbia & Montenegro (1994) and Bosnia & Herzogovina (1998). Czechoslovakia becomes the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the 1994 issue. The Soviet cinema is a presence from the first issue following the so-called ‘Thaw’ from the mid-fifties to the early sixties, then mostly stagnation under Brezhnev overtaken by Glasnost and Perestroika in the late eighties with several years hiatus in reports from Russia in the nineties following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Separate reports follow from Latvia (1994), Georgia, Lithuania (1995), Estonia (1997) Kazakhstan (1998) the Ukraine (1999), and Belarus (2004).

In eastern Europe, the Polish, Hungarian and Czech cinemas are all acknowledged in the first issue (1964). Bulgarian and Yugoslav cinemas make their first appearance in the 1970 IFG, the latter subsequently fragmenting into reports from Croatia (1993), Slovenia (1994), Serbia & Montenegro (1994) and Bosnia & Herzogovina (1998). Czechoslovakia becomes the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the 1994 issue. The Soviet cinema is a presence from the first issue following the so-called ‘Thaw’ from the mid-fifties to the early sixties, then mostly stagnation under Brezhnev overtaken by Glasnost and Perestroika in the late eighties with several years hiatus in reports from Russia in the nineties following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Separate reports follow from Latvia (1994), Georgia, Lithuania (1995), Estonia (1997) Kazakhstan (1998) the Ukraine (1999), and Belarus (2004).

In its issues from 1970, the Guide annually reports the continuing sparse presence in international cinema of 20 or so features produced annually in Romania until the 1989 Revolution following which the number of films made are reduced, while a new wave of talented directors such as Cristi Puiu, Cătălin Mitulescu, and Cristian Mungiu emerge in the 2000s simultaneously delivering international critical success and strong acceptance of key films in the home market. In some respects a not dissimilar success story for the Icelandic cinema is related year by year in the IFG beginning in the 1980 issue.

In its issues from 1970, the Guide annually reports the continuing sparse presence in international cinema of 20 or so features produced annually in Romania until the 1989 Revolution following which the number of films made are reduced, while a new wave of talented directors such as Cristi Puiu, Cătălin Mitulescu, and Cristian Mungiu emerge in the 2000s simultaneously delivering international critical success and strong acceptance of key films in the home market. In some respects a not dissimilar success story for the Icelandic cinema is related year by year in the IFG beginning in the 1980 issue.

Hagir Daryoush (1973-82) and Jamal Omid (1991-2008) report, ‘from the inside’, the extraordinary rise of the new Iranian cinema beginning in the early seventies and peaking internationally in the late eighties and through the nineties. This is a clear example of incisive reporting year by year over several decades of an emerging cinema in difficult political circumstances.

Hagir Daryoush (1973-82) and Jamal Omid (1991-2008) report, ‘from the inside’, the extraordinary rise of the new Iranian cinema beginning in the early seventies and peaking internationally in the late eighties and through the nineties. This is a clear example of incisive reporting year by year over several decades of an emerging cinema in difficult political circumstances.

In the first years of the Film Guide progress is slow in moving much beyond surveying the established film industries in western Europe, Scandinavia, some key eastern European countries, the USSR and those of the anglosphere, with a token addition of Japan as the then recently uncovered outlier in world art cinema, with Israel and Turkey as a kind of bridge between east and west. The fragmentation and underdevelopment of film production on the African continent which at last count is made up of 54 sovereign states, resisted orderly progress.

In the first years of the Film Guide progress is slow in moving much beyond surveying the established film industries in western Europe, Scandinavia, some key eastern European countries, the USSR and those of the anglosphere, with a token addition of Japan as the then recently uncovered outlier in world art cinema, with Israel and Turkey as a kind of bridge between east and west. The fragmentation and underdevelopment of film production on the African continent which at last count is made up of 54 sovereign states, resisted orderly progress.

Over its five decades of publication IFG, year by year is reporting the evolving national production histories of what in certain respects are bifurcated as the Black African cinemas of Francophone north and west Africa and of Anglophone central and east Africa.

Over its five decades of publication IFG, year by year is reporting the evolving national production histories of what in certain respects are bifurcated as the Black African cinemas of Francophone north and west Africa and of Anglophone central and east Africa.

In the ninth edition (1972) the surveys of cinema in three African states – Niger, Senegal, and South Africa – appear for the first time followed by the Arab cinemas of Tunisia (1973), Algeria and Morocco (1979), all three with established histories of film production and distribution in strong film cultures in North Africa. The reports appearing in the final (2012) issue of IFG on these Francophone North African countries, are variously hopeful for the future of film production particularly in Morocco and Tunisia. Egypt by far the largest and only popular cinema in Africa (a peak of 76 features in produced in 1985 down to less than half that in 2012), is surveyed for the first time in 1974, reports temporarily disappearing from IFG’s pages in 1982 and returning in 1987 as a permanent inclusion.

In the ninth edition (1972) the surveys of cinema in three African states – Niger, Senegal, and South Africa – appear for the first time followed by the Arab cinemas of Tunisia (1973), Algeria and Morocco (1979), all three with established histories of film production and distribution in strong film cultures in North Africa. The reports appearing in the final (2012) issue of IFG on these Francophone North African countries, are variously hopeful for the future of film production particularly in Morocco and Tunisia. Egypt by far the largest and only popular cinema in Africa (a peak of 76 features in produced in 1985 down to less than half that in 2012), is surveyed for the first time in 1974, reports temporarily disappearing from IFG’s pages in 1982 and returning in 1987 as a permanent inclusion.

In the 1975 issue, eleven African countries are grouped together – six of which are described as having “no organised film industry” although four Francophone countries – Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Mali and Niger – are noted as having significant independent feature film production with Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, and Tunisia identified as having nationalised or partly nationalised film production. Reports on most of these eleven countries subsequently appear either on a semi-regular or irregular basis. In 1984 Roy Armes in fuller reports on the Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger and Upper Volta/Burkina Faso provides some institutional background for African cinema.

In the 1975 issue, eleven African countries are grouped together – six of which are described as having “no organised film industry” although four Francophone countries – Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Mali and Niger – are noted as having significant independent feature film production with Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, and Tunisia identified as having nationalised or partly nationalised film production. Reports on most of these eleven countries subsequently appear either on a semi-regular or irregular basis. In 1984 Roy Armes in fuller reports on the Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger and Upper Volta/Burkina Faso provides some institutional background for African cinema.

Historically France has been much more active (if this is not without issues of political and aesthetic influence) in supporting film production in its former West African colonies than is the case with the former non-Francophone colonisers, most notably Britain, elsewhere in Africa. Surprisingly, given its compounding political and economic problems, regular reports of the continuing struggle to make films in Zimbabwe appear in IFG through the nineties, the first report appearing in 1993. This struggle to maintain any meaningful film production beyond the use of locations by foreign productions seems symptomatic of the wider issues of weighing on domestic film production across much of Africa.

Historically France has been much more active (if this is not without issues of political and aesthetic influence) in supporting film production in its former West African colonies than is the case with the former non-Francophone colonisers, most notably Britain, elsewhere in Africa. Surprisingly, given its compounding political and economic problems, regular reports of the continuing struggle to make films in Zimbabwe appear in IFG through the nineties, the first report appearing in 1993. This struggle to maintain any meaningful film production beyond the use of locations by foreign productions seems symptomatic of the wider issues of weighing on domestic film production across much of Africa.

Parallel are the ongoing reports (the first in 1990) of film culture in one of the poorest African countries, land-locked Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta) noted for the quality of its state-sponsored feature films and the home of FESPACO, the biennial pan-African film festival, which began in 1969, concurrent with MICA, an international market for African film. The familiar situation is that distribution and exhibition in Burkina Faso, as reported in the nineties, continues to be dominated by American films. African productions during 1994-7 accounting for less than one per cent of the cinema audience (BF with only ten film halls) despite international recognition in festival awards for films by Gaston Kaboré (Zan Boko) and Idrissa Ouedraogo (The Choice, Yaaba) following the ground broken by the earlier release of films by Senegal‘s Ousmane Sembene (Black Girl, Xala) and Djibril Mambéty (Touki Bouki). Mauritania, without an institutional framework or a production report in any of IFG’s 48 issues, was the site for the filming of several of the most acclaimed films (French financed) of Black African cinema: Med Hondo‘s Soleil O (1967) and Sarraounia (1986) and Sissako‘s Timbuktu (2014).

Parallel are the ongoing reports (the first in 1990) of film culture in one of the poorest African countries, land-locked Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta) noted for the quality of its state-sponsored feature films and the home of FESPACO, the biennial pan-African film festival, which began in 1969, concurrent with MICA, an international market for African film. The familiar situation is that distribution and exhibition in Burkina Faso, as reported in the nineties, continues to be dominated by American films. African productions during 1994-7 accounting for less than one per cent of the cinema audience (BF with only ten film halls) despite international recognition in festival awards for films by Gaston Kaboré (Zan Boko) and Idrissa Ouedraogo (The Choice, Yaaba) following the ground broken by the earlier release of films by Senegal‘s Ousmane Sembene (Black Girl, Xala) and Djibril Mambéty (Touki Bouki). Mauritania, without an institutional framework or a production report in any of IFG’s 48 issues, was the site for the filming of several of the most acclaimed films (French financed) of Black African cinema: Med Hondo‘s Soleil O (1967) and Sarraounia (1986) and Sissako‘s Timbuktu (2014).

Chad, formerly part of French Equatorial Africa, like Burkina Faso, is landlocked and amongst the world’s poorest countries. Plagued by corruption and civil strife Chad has its first IFG report as a note in 2009 on the strength of several Chadian filmmakers living and working in Paris, most notably Mahamat Saleh Haroun (A Screaming Man, Bye Bye Africa), and journalist, tv presenter, community activist and documentary filmmaker Zara Mahamet Yacoub. The first African feature film to be directed by a woman – Sarah Maldoror – was Sambizanga (1972). Set during the civil war in Angola in the sixties, it won international attention and critical acclaim through film festival screenings. The Angolan industry was reported in IFG (2009), as beginning to revive after the end of civil war in 2002.

Chad, formerly part of French Equatorial Africa, like Burkina Faso, is landlocked and amongst the world’s poorest countries. Plagued by corruption and civil strife Chad has its first IFG report as a note in 2009 on the strength of several Chadian filmmakers living and working in Paris, most notably Mahamat Saleh Haroun (A Screaming Man, Bye Bye Africa), and journalist, tv presenter, community activist and documentary filmmaker Zara Mahamet Yacoub. The first African feature film to be directed by a woman – Sarah Maldoror – was Sambizanga (1972). Set during the civil war in Angola in the sixties, it won international attention and critical acclaim through film festival screenings. The Angolan industry was reported in IFG (2009), as beginning to revive after the end of civil war in 2002.

In Nigeria the “Nollywood” phenomenon is outlined in successive IFGs from 2006-12 as a multi million dollar “home industry” – thousands of titles of pulp fiction cheaply produced on videocassette sold by pirates on street stalls in the 90s, and on digital video in the 2000s which Dudley Andrew describes as an “anti-global phenomenon of stupendous proportions, worth a place in a course on world cinema…. rich anthropological material, a vibrant folk expression, grassroots graffiti, not meant for viewers outside the community.”(1) It is repeated on a smaller scale elsewhere mainly in other former Anglophone colonies, e.g., Uganda (“Ugawood”), Tanzania (“bongo films”), Ghana (“Gollywood”), Kenya, and Zimbabwe and also in Francophone West African countries such as Benin (formerly Dahomey). A counter reaction in the 2000s resulted in some professionalism being reinstated in Nigerian film production on DV and the first film for many years made on 35mm film.

In Nigeria the “Nollywood” phenomenon is outlined in successive IFGs from 2006-12 as a multi million dollar “home industry” – thousands of titles of pulp fiction cheaply produced on videocassette sold by pirates on street stalls in the 90s, and on digital video in the 2000s which Dudley Andrew describes as an “anti-global phenomenon of stupendous proportions, worth a place in a course on world cinema…. rich anthropological material, a vibrant folk expression, grassroots graffiti, not meant for viewers outside the community.”(1) It is repeated on a smaller scale elsewhere mainly in other former Anglophone colonies, e.g., Uganda (“Ugawood”), Tanzania (“bongo films”), Ghana (“Gollywood”), Kenya, and Zimbabwe and also in Francophone West African countries such as Benin (formerly Dahomey). A counter reaction in the 2000s resulted in some professionalism being reinstated in Nigerian film production on DV and the first film for many years made on 35mm film.

With the increased coverage of the world production survey the number of African countries included peaked in 2009 at 32 of the total of the 54 sovereign African states in seven main plus 25 shorter reports.

With the increased coverage of the world production survey the number of African countries included peaked in 2009 at 32 of the total of the 54 sovereign African states in seven main plus 25 shorter reports.

Until 1969 Japan was the only Asian country represented in the survey when India appearing for the first time followed by Malaysia, Pakistan (1971) China (1973) Ceylon/Sri Lanka (1974), Indonesia (1975), Hong Kong & Taiwan (1976), Bangladesh (1978), the Philippines, Thailand (1979), South Korea (1981), Singapore (1984), Vietnam (1988) and Nepal (2000). In the 1982 issue is the first report of the post Mao relaxation of political control on Chinese cinema and its circulation with an initial retrospective of more than thirty features including previously unseen features from the 1930s and including films shelved after the Revolution. The retrospective was screened at London’s National Film Theatre and subsequently at festivals and cinematheques in LA, San Francisco, Cannes, Amsterdam and Melbourne. In 1987 Derek Elley announced, in IFG, 1985 as the breakthrough year for Chinese cinema with the release of the first “fifth generation” film, Yellow Earth.

Until 1969 Japan was the only Asian country represented in the survey when India appearing for the first time followed by Malaysia, Pakistan (1971) China (1973) Ceylon/Sri Lanka (1974), Indonesia (1975), Hong Kong & Taiwan (1976), Bangladesh (1978), the Philippines, Thailand (1979), South Korea (1981), Singapore (1984), Vietnam (1988) and Nepal (2000). In the 1982 issue is the first report of the post Mao relaxation of political control on Chinese cinema and its circulation with an initial retrospective of more than thirty features including previously unseen features from the 1930s and including films shelved after the Revolution. The retrospective was screened at London’s National Film Theatre and subsequently at festivals and cinematheques in LA, San Francisco, Cannes, Amsterdam and Melbourne. In 1987 Derek Elley announced, in IFG, 1985 as the breakthrough year for Chinese cinema with the release of the first “fifth generation” film, Yellow Earth.

In terms of number of feature films produced, the world’s largest film industry, India, had to wait until the sixth issue of IFG in 1969 for a report covering the national Hindi cinema centred in Mumbai (“Bollywood”), South Indian Tamil cinema centred in Chennai, and a multiplicity of cinemas in regional languages such as Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Marathi, and Bengali. Mention is made in the IFG report of an “Indian avant-garde” in the wake of the success at international film festivals of Satyajit Ray‘s films (in Bengali) bringing to notice most notably the work of Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and Buddhadeb Dasgupta. In the following (1970) issue of IFG, Sen’s Bhuvan Shome is described as “free from influences… unlike anything yet done in India.” In her report on 2010, as “a lacklustre year” at the box office for Bollywood blockbusters, Uma Da Cunha, who had been reporting on Indian cinema in the IFG each year since 1977, and having earlier reported on Shyam Benegal‘s pathbreaking merging of popular narrative and art film, finds promise, both with domestic and international audiences, in a small but growing number of films directly portraying contemporary life.

In terms of number of feature films produced, the world’s largest film industry, India, had to wait until the sixth issue of IFG in 1969 for a report covering the national Hindi cinema centred in Mumbai (“Bollywood”), South Indian Tamil cinema centred in Chennai, and a multiplicity of cinemas in regional languages such as Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Marathi, and Bengali. Mention is made in the IFG report of an “Indian avant-garde” in the wake of the success at international film festivals of Satyajit Ray‘s films (in Bengali) bringing to notice most notably the work of Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and Buddhadeb Dasgupta. In the following (1970) issue of IFG, Sen’s Bhuvan Shome is described as “free from influences… unlike anything yet done in India.” In her report on 2010, as “a lacklustre year” at the box office for Bollywood blockbusters, Uma Da Cunha, who had been reporting on Indian cinema in the IFG each year since 1977, and having earlier reported on Shyam Benegal‘s pathbreaking merging of popular narrative and art film, finds promise, both with domestic and international audiences, in a small but growing number of films directly portraying contemporary life.

The first reference to Latin American cinema in IFG was a paragraph summarising film production across the continent in the second issue in 1965. The annual IFG surveys of the three largest film industries in Latin America begin with Brazil in 1970, Argentina (1972) and Mexico (1973) – coinciding with the emergence of Brazil’s cinema novo, Argentina’s parallel cinema and the leftist cinema in Chile during the ill-fated Allende government (1972) – radical film movements together with the Ukamau Group in Bolivia (1972), all in turn influenced by the new film culture of Cuban cinema (75) set up under the film institute, ICAIC, following the Cuban Revolution in 1959. The largely nationalised Mexican cinema operated politically and economically on a very different basis from that of the film industry in Cuba.

The first reference to Latin American cinema in IFG was a paragraph summarising film production across the continent in the second issue in 1965. The annual IFG surveys of the three largest film industries in Latin America begin with Brazil in 1970, Argentina (1972) and Mexico (1973) – coinciding with the emergence of Brazil’s cinema novo, Argentina’s parallel cinema and the leftist cinema in Chile during the ill-fated Allende government (1972) – radical film movements together with the Ukamau Group in Bolivia (1972), all in turn influenced by the new film culture of Cuban cinema (75) set up under the film institute, ICAIC, following the Cuban Revolution in 1959. The largely nationalised Mexican cinema operated politically and economically on a very different basis from that of the film industry in Cuba.

In addition to the annual surveys on the state of the national production there are dossiers on selected national cinemas:

- 1985 – French Cinema Now- the ‘second wave’ (27pp)

- 1986 – Australian (21pp)

- 1987 – Canadian (36pp)

- 1988 – Scandinavian (61pp)

- 1989 – Soviet (42pp) – this pre-dates the collapse of the USSR with the first dossier appearing as Russia in 1993

- 1990 – Spanish (37pp)

- 1991 – New Zealand (32pp)

- 1992 – Italian (38pp)

- 1992 – Focus on the Baltic Republics (11pp)

- 1993 – Major Focus on Iranian Cinema (27pp)

- 1993 – Greek Cinema: the Latest Decade (16pp)

- 1994 – Argentine Cinema Now (28pp)

- 1995 – Polish (24pp)

- 1998 – Spanish (20pp)

- 2003 – Greek (10pp)

- 2004 – Iranian Cinema Now (15pp)

- 2006 – Irish (12pp)

- 2008 – German (14pp)

- 2009 – Focus on Israel (6pp)

For ten issues, 1999-2009, a world box office section is belatedly included in the IFG listing the top ten grossing features in a selection of between 30-40 countries and market share of domestic production for selected countries. Wikipedia now offers a more complete up-to-date survey, by country, of number of films produced and their share of the domestic market.

Film festivals

In the 40th edition (2003) the rise of the international film festival is seen as perhaps the most notable institutional development in film culture during these five decades. (2) “They have proliferated to such a degree as to effectively drive the small exhibitor from the market place yet pay little or nothing in rentals to the distributor or [producer] of the films.”(3) Major festivals and awards are listed each year (15 festivals on 15pages in 1964 expanded to more than 200 on 72 pages in 2012),

In the 40th edition (2003) the rise of the international film festival is seen as perhaps the most notable institutional development in film culture during these five decades. (2) “They have proliferated to such a degree as to effectively drive the small exhibitor from the market place yet pay little or nothing in rentals to the distributor or [producer] of the films.”(3) Major festivals and awards are listed each year (15 festivals on 15pages in 1964 expanded to more than 200 on 72 pages in 2012),

Longer tributes to individual festivals were introduced in 1986 with the Sydney Film Festival followed by Locarno, San Francisco (both 1987), Telluride (1988), Montreal (1989), Berlin Film Forum (1990),Toronto (1991), International Tournee of Animation (1992), London (1993), Valladolid (1994), La Rochelle (1995), Hong Kong (1996), Norwegian (1997), Mill Valley (1998), Flanders (1999), Thessaloniki (2000), Karlovy Vary (2001), Denver (2002), Berlinale (2006 and 2010) and Sundance (2009). In the 1984 issue, David Stratton provides a personal view in “Film Festivals I Have Known and Loved.”

Longer tributes to individual festivals were introduced in 1986 with the Sydney Film Festival followed by Locarno, San Francisco (both 1987), Telluride (1988), Montreal (1989), Berlin Film Forum (1990),Toronto (1991), International Tournee of Animation (1992), London (1993), Valladolid (1994), La Rochelle (1995), Hong Kong (1996), Norwegian (1997), Mill Valley (1998), Flanders (1999), Thessaloniki (2000), Karlovy Vary (2001), Denver (2002), Berlinale (2006 and 2010) and Sundance (2009). In the 1984 issue, David Stratton provides a personal view in “Film Festivals I Have Known and Loved.”

Wikipedia estimates there are over 3,000 now active film festivals worldwide.

The digital revolution

In considering the implications of the changes being wrought by digital technology in production, distribution, exhibition, and preservation, the editorial response of IFG was more reactive than exploratory .

In considering the implications of the changes being wrought by digital technology in production, distribution, exhibition, and preservation, the editorial response of IFG was more reactive than exploratory .

From the first issue, as already noted the IFG documents and supports art house cinemas in parallel with the core commitment to document the internationalisation of film production. By the 1988 issue, as also previously noted, specialist film exhibition is seen to be threatened with near extinction by the home videocassette and advent of the multiplex. In 1995 IFG commits sixteen pages to supporting the US video industry’s new commitment to expanding the relatively small but quality-conscious audience for laser discs concentrated in the US. In technical presentation LDs then represented “the closest experience to theatrical viewing to be achieved in the home.”

From the first issue, as already noted the IFG documents and supports art house cinemas in parallel with the core commitment to document the internationalisation of film production. By the 1988 issue, as also previously noted, specialist film exhibition is seen to be threatened with near extinction by the home videocassette and advent of the multiplex. In 1995 IFG commits sixteen pages to supporting the US video industry’s new commitment to expanding the relatively small but quality-conscious audience for laser discs concentrated in the US. In technical presentation LDs then represented “the closest experience to theatrical viewing to be achieved in the home.”

In the tenth issue of IFG in 1973 there is an editorial reference to the impending revolution in the way films might be accessed by cable tv and the video cassette. In 1975 a four-page section is specifically devoted to “TV cassettes, Discs etc.” Questions surround the competing claims of video tape widths, of tape versus disc, recording versus replay, constant revision of available options and looming unresolved copyright issues. By 1981 the editor is confidently predicting that the expansion of the videocassette market and the development of the video disc is not only providing a growing new income stream from the sale of cassettes and discs, but it “could revive the taste for film going among people who long ago abandoned the habit.” The boom in cable TV in America is noted the following year as not having had an immediately negative effect on cinema attendances in 1981.

In the tenth issue of IFG in 1973 there is an editorial reference to the impending revolution in the way films might be accessed by cable tv and the video cassette. In 1975 a four-page section is specifically devoted to “TV cassettes, Discs etc.” Questions surround the competing claims of video tape widths, of tape versus disc, recording versus replay, constant revision of available options and looming unresolved copyright issues. By 1981 the editor is confidently predicting that the expansion of the videocassette market and the development of the video disc is not only providing a growing new income stream from the sale of cassettes and discs, but it “could revive the taste for film going among people who long ago abandoned the habit.” The boom in cable TV in America is noted the following year as not having had an immediately negative effect on cinema attendances in 1981.

“Following the template for special effects set by Star Wars in 1977,” it is further noted that by the millennium “acronyms like CGI and DV have entered the argot of film fans everywhere.” In the issue of IFG in 2003 it is further acknowledged that the laser-disc and the videocassette have been superseded by the DVD which it is claimed has been adopted by the consumer more rapidly than any other technology in history, a marketing and technical accomplishment spectacularly overtaken less than two decades later by the iPhone. In 2003 IFG included an 8 page “DVD Round-Up” for the first time.

“Following the template for special effects set by Star Wars in 1977,” it is further noted that by the millennium “acronyms like CGI and DV have entered the argot of film fans everywhere.” In the issue of IFG in 2003 it is further acknowledged that the laser-disc and the videocassette have been superseded by the DVD which it is claimed has been adopted by the consumer more rapidly than any other technology in history, a marketing and technical accomplishment spectacularly overtaken less than two decades later by the iPhone. In 2003 IFG included an 8 page “DVD Round-Up” for the first time.

IFG’s five decades

The concept of art cinema provides a discursive range of cinematic spaces to survey and critique. The IFG constituted a possible entry point, potentially deploying the flexibility of the concept to allude to its global development from Eurocentric origins through varying ‘local’ manifestations.

The concept of art cinema provides a discursive range of cinematic spaces to survey and critique. The IFG constituted a possible entry point, potentially deploying the flexibility of the concept to allude to its global development from Eurocentric origins through varying ‘local’ manifestations.

IFG’s initial focus was, as noted, a cinephilac one: to facilitate the growth of specialist art house cinemas primarily at European and anglosphere locations through wider, in depth, distribution. At the same time the potential of the world production survey for broadening sources of art cinema was recognised by the continual expansion of its coverage.

IFG’s initial focus was, as noted, a cinephilac one: to facilitate the growth of specialist art house cinemas primarily at European and anglosphere locations through wider, in depth, distribution. At the same time the potential of the world production survey for broadening sources of art cinema was recognised by the continual expansion of its coverage.

Although ‘art film’ and ‘national’ are fluid concepts, this is never discussed beyond the former being designated by the editor as ‘serious cinema’. Practicalities required that, for the purposes of the survey, nation states are designated as synonymous with the national when this can be culturally problematic evident in examples referred to herein: the break-up of former Yugoslavia, the collapse and break up of the USSR, and operation of political, and cultural spheres of influence through a form of cultural hegemony such as between the US and Latin American states, and France and her former colonies in West Africa.

Although ‘art film’ and ‘national’ are fluid concepts, this is never discussed beyond the former being designated by the editor as ‘serious cinema’. Practicalities required that, for the purposes of the survey, nation states are designated as synonymous with the national when this can be culturally problematic evident in examples referred to herein: the break-up of former Yugoslavia, the collapse and break up of the USSR, and operation of political, and cultural spheres of influence through a form of cultural hegemony such as between the US and Latin American states, and France and her former colonies in West Africa.

Through its five decades the IFG developed as a compact source of information on trends in the international circulation of art film as “a geographically organised force field” centred on a European-American critical, institutional and industrial infrastructure but increasingly admitting to the field filmmakers in previously outlying cinematic industries and cultures being adjudged as near exemplary for festival and art-house exposure.

Through its five decades the IFG developed as a compact source of information on trends in the international circulation of art film as “a geographically organised force field” centred on a European-American critical, institutional and industrial infrastructure but increasingly admitting to the field filmmakers in previously outlying cinematic industries and cultures being adjudged as near exemplary for festival and art-house exposure.

Reports, most often by correspondents written from the ‘inside’, gained value by being juxtaposed annually together in a single volume. The Guide, as noted, is prescient in recognising the growing institutional and critical role of the expanding film festival network in this process of globalisation.

Reports, most often by correspondents written from the ‘inside’, gained value by being juxtaposed annually together in a single volume. The Guide, as noted, is prescient in recognising the growing institutional and critical role of the expanding film festival network in this process of globalisation.

It is only during its last decade that the Guide seemed to become more settled in its mapping of the terrain.

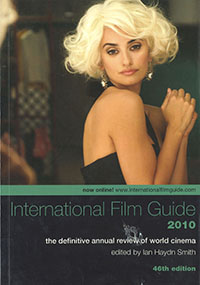

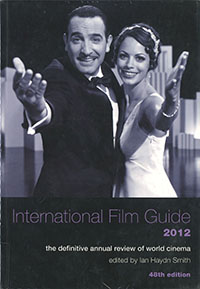

While advertising provided substantial revenue predominantly from the industry, government and other sponsoring agencies and film festivals with arrival of the internet the Film Guide‘s on-going viability would seemed to have become increasingly dependent on sponsorship, first by the “Variety empire,” 1990 -2006, and then briefly by Turner Classic Movies in 2008. The decline in the number of advertisers is noticeable in the last two issues. The deferment of publication of the 2007 issue to 2008, coinciding with the end of the Variety sponsorship, meant that the 2012 IFG was still two issues short of the fifty year milestone which would have been a time for review and reflection on what had been a path-breaking approach to documenting an evolving world art cinema.

While advertising provided substantial revenue predominantly from the industry, government and other sponsoring agencies and film festivals with arrival of the internet the Film Guide‘s on-going viability would seemed to have become increasingly dependent on sponsorship, first by the “Variety empire,” 1990 -2006, and then briefly by Turner Classic Movies in 2008. The decline in the number of advertisers is noticeable in the last two issues. The deferment of publication of the 2007 issue to 2008, coinciding with the end of the Variety sponsorship, meant that the 2012 IFG was still two issues short of the fifty year milestone which would have been a time for review and reflection on what had been a path-breaking approach to documenting an evolving world art cinema.

Related page: International Film Guide’s Five Directors of the Year 1964-2012

Notes

1. In his foreword (q.v.) Dudley Andrew extends a term – optique – that he had devised to distinguish particular styles in the 1930s, to also distinguish “larger contexts affecting production, reception and film culture.” He sees three optiques “that have been operating for a very long time, even while technological and social developments have caused them to vary”: (1) national folk films (Nollywood being an example), (2) global entertainment films (Hollywood dominant), and (3) international art cinema (the concept a domain of critics and film festivals).

2. The IFG did not acknowledge the role of annual national film festivals dedicated to showcasing selected recent releases of that national cinema, most often with semi-government support from the country concerned and commercial sponsorship. They have steadily increased in number in major metropolitan centres during the last two decades or so pre-empting or supplementing some of the role of international film festivals.

3. It is only well into the 2000s that film festivals paying rentals became widespread.

Select reading

- Andrew, Dudley “Foreword” Global Art Cinema ibid, pp.v-xii

- Bordwell, David “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice” Film Criticism 1 1979 expanded in Narration in the Fiction Film Uni of Wisconsin Press 1985 ch. 10

- Ellis, John “Art, culture and quality: terms for a cinema in the 40s and 70s” Screen SEFT v19/3 1978

- Crofts, Stephen, “Concepts of National Cinema” in The Oxford Guide to Film Studies, ed. John Hill and Pamela Church Gibson, Oxford University Press 1998 pp.385-94

- Galt, Rosalind and Karl Schoonover, “Introduction: The Impurity of Art Cinema” in Global Art Cinema, eds. Galt and Schooner, OUP, 2010 pp.7-27

- Neale, Steve, “Art Cinema as an Institution” Screen v22/1 1981

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey “Art Cinema” in The Oxford History of World Cinema OUP 1996 pp. 567-75

Thanks to Adrienne McKibbins for clarifying aspects of contemporary Indian cinema.

World Cinema in Wikipedia

Wikipedia provides a basic historical framework for a comprehensive list of world cinema by nation-state as well as an up- dating of basic statistics. The annual IFG survey stands as a complementary documentation of the changing terrain of an emergent international art cinema, 1963-2011.